The most important single aspect of software development is to be clear about what you are trying to build. - Bjarne Stroustrup (inventor of c++)

Plans are worthless, but planning is everything. - Dwight D. Eisenhower

I was once on an intern team tasked with detecting open parking spots with cameras. This team had a “just code” mentality. Code was the metric that mattered and taking time to get on the same page, better understand the problem, or test was just slowing us down.

We did turn out code fast. However, we reached the end of the summer with none of our goals met. With no unified understanding, each coder worked on their own assumptions. Different parts of the code base served different markets and were essentially different products.

By the time we considered requirements, the code didn’t work, didn’t address the intended use, and it was too late to fix.

Requirements First

Requirements are the first step of any project.

The above intern project failed because we never considered what we were accomplishing, in other words, our requirements. Requirements set out the vision, and we had none. With no vision, the software had no where to go from the start.

This isn’t unique to interns. Fred Brooks suggests the danger for professionals is more building the wrong thing than building the thing wrong (Design of Design, p.168).

Requirements are software’s blueprint. Clear requirements allow a team to work with unified intent, making decisions that fit the whole. They define the goals, scope, and outcomes, making sure the needs are met before the solution is built. It also prevents unnecessary work. Studies show fixing errors is 10 to 100 times cheaper in requirements than published code (Code Complete p. 28).

Conversely, unclear requirements make unclear software. Code is precise and, like build a building, every detail will be filled one way or the other. If intent is unclear, decisions will be filled with assumptions. To paraphrase Pragmatic Programmer, if you aren’t programming intentionally, you are programming by accident.

Check Frequently

Stable requirements are bad, because the only time requirements are stable is when a product is dead.

The world doesn’t stand still. Customer needs, problem understanding, software frameworks, and hardware are a few of the factors that can lead to shifting requirements.

This means requirements must be checked regularly. Research directly links contact frequency with customers to product quality (How to Build Products Users Love). The minimum is 2 hours every 6 weeks. Any less and quality will decline over time.

Pragmatic Programmer uses the analogy of a boiled frog. Proverbially, a frog won’t notice if you heat water a bit at a time. Eventually, the water boils and the frog is… in hot water.

Don’t be the frog, check assumptions regularly.

How Much

Requirements are critical to project success, should be considered upfront, and they need modified frequently. That may sound overbearing, but it doesn’t need to be. The amount of planning depends on the project and is more art than science.

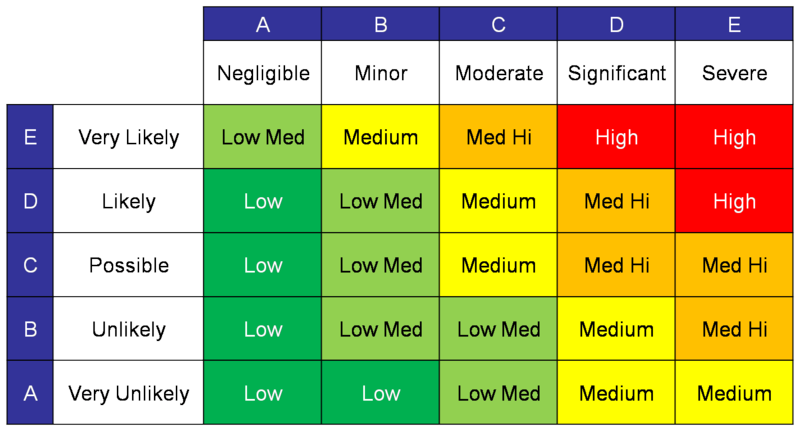

It may be useful to employ a threat matrix. This is a simple tool for evaluating importance by considering likelihood and severity of failure.

Building a single-use script for a personal task is low impact and low use, so it doesn’t need much planning. On the other hand, an airplane control system should probably have more planning and verification than coding.

In general, up front planning should identify the most important features, not all features. There should be enough clarity that, if a mockup was made, everyone could agree that the goals were represented.

Eisenhower says, “plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” Plans will likely be wrong in some way, but planning is still needed to set direction, operate cohesively, and correct effectively.

Afterward, iterate. Peel back the layers of detail one at a time. Identify the most important concerns for the current state of the project and define them clearly. It is better wrong than vague, because clear statements can be debated and corrected, vague ones wont (Fred Brooks).

Requirement Collection

Requirements stem from understanding customer needs. That means knowing who the customer is. It may be you, it may be consumers, co-workers, businesses, etc.

With customer identified, there are many tools for extracting requirements. Here are a few.

Interviews: Directly talking with the customer. Good for getting a high-level understanding or when there are a few or knowledgeable customers. Be careful, customers don’t always understand their need or know how to translate it to software.

Shadowing: Passively observe the customer in their normal routine. Good at uncovering habits and small details that the customer may not even register.

Surveys: A normalized set of questions, preferably quantitative. Good for uncovering trends in a large group.

Support: Handling questions and issues encountered by users. Support is the front-line of communication with current customers. It is especially good at uncovering errors and difficult user experiences. Good support improves software quality and makes users feel valued and listened to. Wufoo attributes much of their success to support driven development.

TL;DR

Requirements are central to building useful software. They set a unified vision and define outcomes, making sure the needs are met and collaborators are aligned.

Requirements should be considered upfront, and periodically, to keep expectations aligned. The magnitude of effort depends on the impact of the task and probability of issues.

Many tools exist for extracting requirements with customers. Identify your customer and communicate with them frequently.

Further Reading

- Code Complete, Steve McConnell, Ch 3: Measure Twice, Cut Once

- How to Build Products Users Love, Kevin Hale, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sz_LgBAGYyo

- Design of Design, Fred Brooks, Ch. 11 Constraints are Friends, Ch. 14 How Expert Designers Go Wrong

- Agile Principles, Patterns, and Practices, Robert Martin, Ch. 3 Planning

- Pragmatic Programmer, Andy Hunt and David Thomas, Section 37 Solving Impossible puzzles, Section 36 The Requirements Pit, Section 4 Good-Enough Software