Continuing the event storm explorations, I tested out several approaches for translating event storms into system designs.

Event Storming Review

For those who are unfamiliar, event storming is a technique for mapping out processes. It’s used to create a shared picture between people of many different roles.

An event storm is primarily composed of events. Events represent something that happened that other parts of the business might need to know about. Some examples from an ecommerce site might include OrderCanceled, OrderPacked, and OrderShipped.

Alberto published an excellent and brief introduction to event storming. You can also checkout Awesome Event Storming for more materials and examples.

Problem Context

I’ve been exploring event storming with some other developers. We’ve previously completed the high-level event storm (process flow using sticky notes) and clarified key flows using data models. Now we want to translate the event storm into a high-level system design.

I’ve written systems based on event storms in the past, but always in a functional programming context. Functional design seemed like too much learning to pile on for others in the current experiment. Here I’ll explore a few other approaches for refining event storms into high-level designs and compare them to the functional approach.

Example Workflow

This post is heavily based on artifacts from previous explorations I’ve replicated the basic artifacts here. For more details please read Event Storming Interaction-heavy Flows and Clarifying Event Storms with Data Modeling.

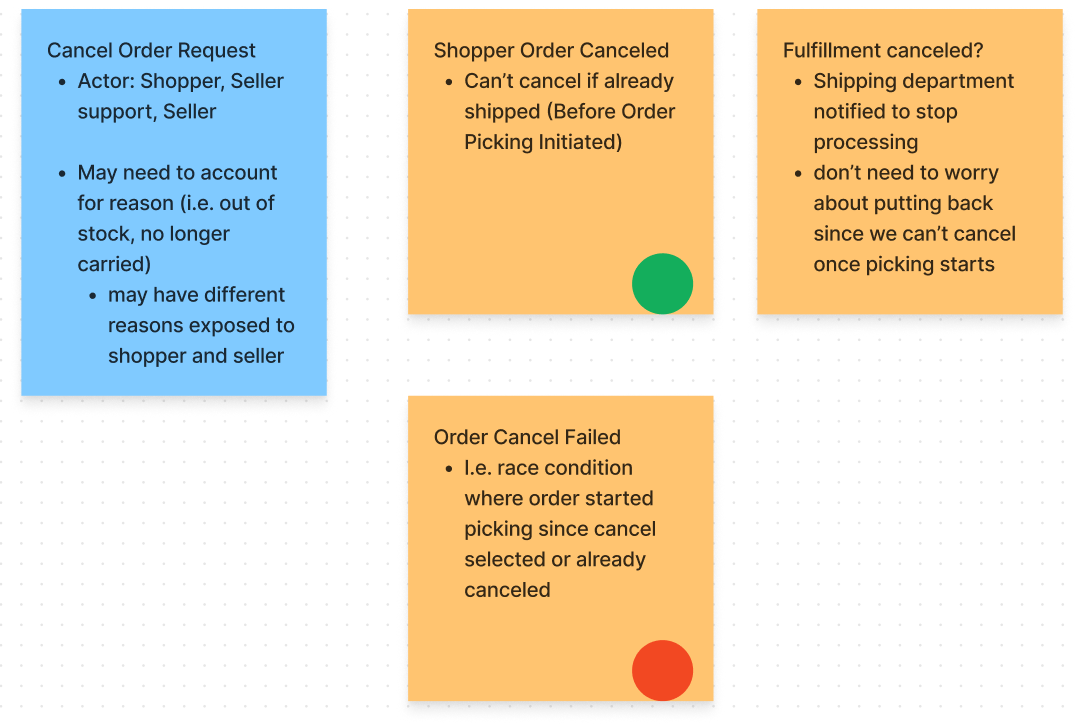

The event storm sticky notes for the Cancel Order flow.

The data model for the Cancel Order flow.

workflow CancelOrder =

input: CancelOrderRequest

output:

| ShopperOrderCanceled

| OrderCancelFailed

data CancelOrderRequest = {

OrderId: OrderId

Reason: ShopperCancelReason

}

data OrderId =

constraints: Should be unique. Doesn't need to be human readable.

data ShopperCancelReason = // TODO

data ShopperOrderCanceled = // TODO

data OrderCancelFailed = // TODO

Start with the data model

The stakeholder-focused data model is a very good starting point for a software design. It specifies data, constraints on that data, and workflow inputs/outputs that can translate to action signatures.

In essence, this originally stakeholder-focused model has defined our high-level system endpoints.

But, we still need to know what dependencies those high-level endpoints will need, what concerns should be reused, how all of it should be organized into modules, etc.

This is where I hoped to side-step functional programming, but let’s see the functional version for reference.

Event-Driven Architecture

Event storms leverage events to model business processes. Well, there’s also a software design paradigm based on events: Event-Driven Architecture. Specifically, I’ll focus on a functional-core type design.

Sneaky Code

The data model has thus far been focused on redability and collaboration. It was largely a convenient translation of our event sticky notes into text that could be progressively clarified alongside non-developers.

Turns out, with the right software design, this model effectively is a high-level code model.

Here’s the non-developer friendly model we defined previously

workflow CancelOrder =

input: CancelOrderRequest

output:

| ShopperOrderCanceled

| OrderCancelFailed

data CancelOrderRequest = {

OrderId: OrderId

Reason: ShopperCancelReason

}

data OrderId =

constraints: Should be unique. Doesn't need to be human readable.

data ShopperCancelReason = // TODO

data ShopperOrderCanceled = // TODO

data OrderCancelFailed = // TODO

Suppose we tweak this model syntax just a bit

->indicates a transformation. For example,CancelOrderRequest -> CancelOrderResultmeans take a CancelOrderRequest and return a CancelOrderResult*indicatesANDwhen a flow requires multiple pre-conditions- We replace

workflowanddatawithtype

Now the model would look like this

| |

Surprise! This is valid F# syntax (minus the order of type declarations, which I left alone to keep the comparison easy).

Functional Core

The code design approach here is called Functional Core. It also leans on Event-Driven Architecture ideas.

The idea is that the business rules are pure functions, they don’t cause any observable state change. Any changes must be reflected in the function’s return value. The return value in this case is the event data structures. The events represent state changes that can be persisted by simple mapping functions.

This approach is very intersting, but I won’t go very deep here. Domain Modeling Made Functional is excellent resource for futher exploration. The book is a fantastic introduction to domain modeling, event storming, or just a thoughtful requirements-driven development process. The book is very approachable and I highly recommend it, but you can also check out his free presentation or his related Designing with Types series. His work is where I learned many of the ideas discussed in this post. Mark Seemann also has good content on this approach (book, blog).

The main thing to know for now is that this approach is my reference point for how well event storms can map to code.

Dependencies

We showed that the domain-focused data model maps well to code, but to flesh out our developer-focused design we also need to consider dependencies. What will each flow need to complete its work and what are the common shared dependencies/activities between flows.

Contemplating dependencies is rather straightforward with a functional-core approach.

Essentially, we just need to consider what information or sub-actions may be needed to translate a command into it’s related events but isn’t present in the input command. For example, the CancelOrderRequest includes only an OrderId, but we may need to analyze items in the order or the current status of the order to decide the outcome.

We can mostly ignore the mundane dependencies like state persistence. The domain rules themselves don’t persist state. Any changes in state will be reflected in the returned events and are rather predictably translated into persisted state with little logic.

Dependencies can be discussed as an extension of the business-focused data model.

workflow CancelOrder =

input: CancelOrderRequest

output:

| ShopperOrderCanceled

| OrderCancelFailed

dependencies:

GetOrderById

// the command doesn't include the full order,

// so we need to be able to look it up

Or, dependencies could be reflected directly into the code translation of the model

| |

Note that F# has partial application (as do many functional languages). This allows us to pass part of the argument list and get back a function on the remaining arguments. This means functions can accept dependencies as arguments without passing them on every function call. It’s a bit like constructor injection, but at a function level.

| |

Aside: Fix State Dependencies Upfront

Re-examining GetOrderById, there’s not much reason the business rule needs a function to get the order. Instead, directly accepting an order allows the flow to fix all its state up front, making observability and error reproduction much easier.

This seems like a good place to diverge from the business model and assume we can get a full order ahead of time.

| |

Note that option allows us to either find an existing order or not. We can let the CancelOrder flow decide what to do if no order exists.

Modularization

Modularization is also simple with an event-driven / functional-core approach.

The workflow signatures stand alone. They can communicate inputs, outputs, and even dependencies in a self-contained fashion (both in the business-oriented model and the F# model).

This means we don’t have to make any decisions about where these functions live in order to explore dependencies. This avoids a potential bias from grouping workflow early on just to get them in classes for dependency management. Instead we can see what dependencies emerge, and inform our modularization at all levels after exploring individual endpoints on their own terms.

The top-level modules will, however, likely be based on business divisions in the event storm. I.e. you could draw circles around groups of sticky notes based on who in the company is responsible for it. Still, analyzing common dependencies might inform hidden connections and who really owns certain workflows.

Other Approaches

Now we’ve seen my baseline process for translating event storms into functional designs. It’s time to explore how other design approaches might work.

Translating to C#

I thought I might be able to use C# to formalize data and dependencies in a similar way as I could with functional-core and F#. I could use interfaces to translate workflows into function signatures, and data-only classes to represent the inputs and outputs. Perhaps a constructor listing dependencies would do for modeling side-effects or state required for a workflow.

Also key, I wasn’t going to use a functional core model, but a Ports and Adapters-style model where the workflows might enact state instead of returning events (i.e. using Dependency Inversion).

This devolved quickly for several reasons. First, C# anonymous functions are not intuitive to read, and interfaces require a name. This prematurely pressures toward grouping command flows into modules or services. It also more clearly makes the model seem like code. The gap between the domain and code model is far enough that it feels weird and effortful.

| |

Second, C# doesn’t have a concise syntax for alternative data cases. We can model the command just fine, but the events would all have to inherit from a base class. It clearly becomes code

| |

In C#, we have to use a constructor or currying if we don’t want to pass dependencies on every function call. This starts pulling us into concrete types and draws more code-specific concerns into the picture.

Overall, C# doesn’t work well as a semi-formal specification. There are too many concerns that force a compromise between C# syntax and avoiding code-specific concerns. This is a deal breaker for working with non-developers, but also tempts developers to preemptively dive into code details.

Translating to F# with stateful dependencies

I thought perhaps a Ports and Adapters-style model would fair better in F# because F# has readable anonymous function types, readable alternative value types, and can partially apply functions to handle dependency management.

However, ports and adapters-style modeling didn’t feel good in F# either. The translation from events to types is less direct because the workflows commit state instead of returning events. The functions also have way more dependencies in order to enact state, which decreases readability.

Most importantly, the added concerns don’t add any modeling benefit, they are purely code concerns.

State management is the most obvious complicating concern. Statefullness through the call stack distributes defensive programming, orchestration, and scaling concerns across many methods. The relationship of all these concerns must be kept in mind and weighs down the modeling process.

It’s much easier to grapple with state decisions when they are concentrated in one layer. In effect, we almost back to a functional-core approach.

Semi-formal Ports and Adapters syntax

I also tried a ports and adapters-style design using a semi-formal syntax, like what was used for the business-focused data model.

The semi-formal language didn’t fair any better than F#. Statefulness still complicated the dependencies and general design considerations. Attempts to simplify effectively led back to the functional-core / event-driven model.

Conclusion: Event-Driven Modeling Wins

My conclusion is that a functional core and event-driven model is the most effective for refining event storms into high level code models.

The translation is clear and only a short step from the non-technical data model. The key concerns at the domain level and high-level design level can be clearly discussed with one model.

An event-based model requires the fewest incidental implementation details or premature decisions while still covering the essential high-level design decisions.

The key difference between functional core and other styles like ports and adapters seems to be state. Statefulness in the domain distributes complicating factors like validation, transactions, and concurrency.

While the simplest model is functional core, the production code can be implemented in a different style if desired. The event model still captures the critical high-level details and translating an event-driven model into other styles is mostly a matter of implementation details.