Event storm sticky notes capture high-level process flow, but different actors in that flow often have specific expectations of each other. This is where high-level data modeling shines.

Event Storming Review

For those who are unfamiliar, event storming is a technique for mapping out processes. It’s often used to create a shared picture between people of many different roles.

An event storm is primarily composed of events. Events represent something that happened that other parts of the business might need to know about. Some examples from an ecommerce site might include OrderCanceled, OrderPacked, and OrderShipped.

Alberto published an excellent and brief introduction to event storming. You can also checkout Awesome Event Storming for more materials and examples. There’s also a brief example below.

Context & What now

I’ve been exploring event storming with some other developers. We’re satisfied with our overall process (modeled mostly with command and event sticky notes). The next step is to dig into portions of the flow and more thoroughly model what different actors expect from each other. Specifically, we’ll elaborate on the sticky note model with a data model.

This stage could be done with smaller groups of stakeholders and is still business-focused (focusing on business modeling, not translation to code). This detailed modeling aims to uncover hidden assumptions and specific dependencies at key parts of the business process.

Uncovering these details might reveal weaknesses or needed changes in the overall event storm model.

Example Workflow

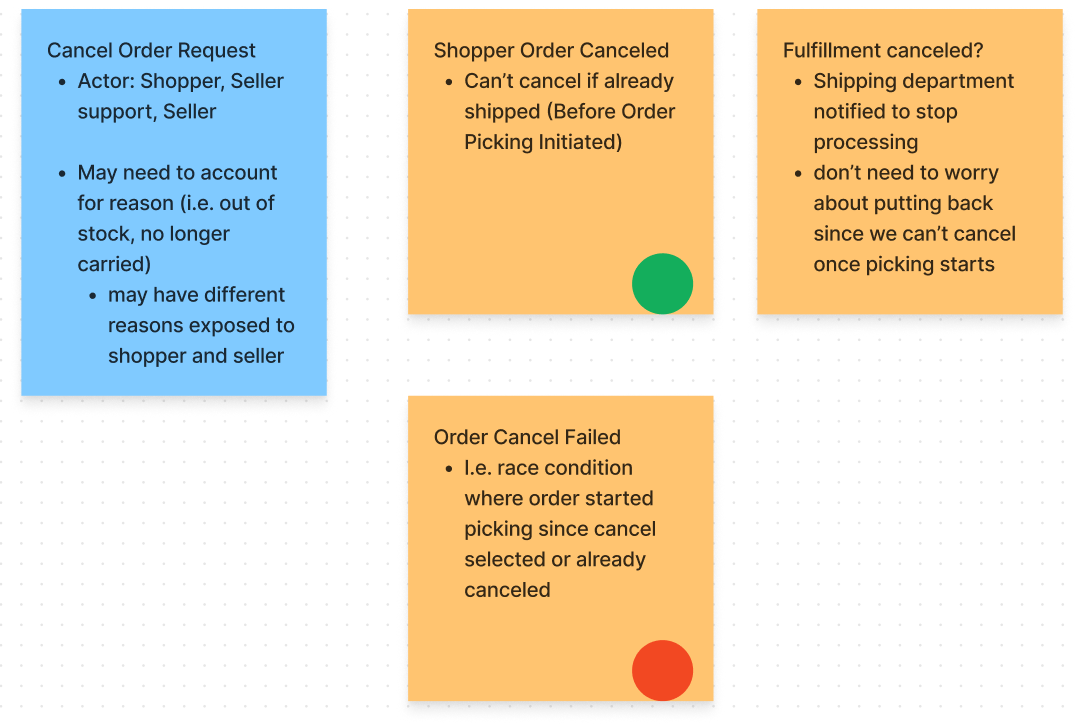

The portion of the event storm we’ll model is shown in the picture above.

This flow consists of one command and the events that follow it. Specifically, the command is Cancel Order Request.

If the command succeeds, then the Shopper Order Canceled event is raised and the Fulfillment Canceled event is also raised. Fulfillment Cancelled could, in the future, be subject to more sophisticated flows that follow from an order cancel. For simplicity, it fulfillment is assumed canceled if the order cancel succeeds.

If the Cancel Order Request fails, an Order Cancel Failed event is thrown with the reason for failure. There aren’t multiple failure events in this case because different modes of failure wouldn’t be handled differently by the business.

Data Modeling

I first learned about event storms from Scott Wlaschin’s Domain Modeling Made Functional, and this process largely follows his example.

Data exploration starts by choosing a high-level workflow, like the one we demonstrated above. We bootstrap our data model by translating the stickynotes to a text-based workflow definition. The workflow uses the command as input and the events as output.

A simple syntax might stub the workflow like this

workflow CancelOrder =

input: CancelOrderRequest

output:

| Shopper Order Canceled

| Order Cancel Failed

Note that | is used as a shorthand for alternatives. Like type Answers = | Yes | No.

Next, start asking what data each of those inputs and outputs include. Stub out child types until you’ve reached the bottom or decided enough detail has been covered.

All of this communicated in some semi-formal language to balance readability with enough clarity to expose gaps in understanding.

For example, we start asking what’s in the CancelOrderRequest

data CancelOrderRequest = {

OrderId: OrderId

Reason: ShopperCancelReason

}

Are there important details for OrderId or ShopperCancelReason?

For example, does OrderId need to be easily readable by customers?

Whatever we find, constraints might be recorded like in this example.

data OrderId =

constraints: Should be unique. Doesn't need to be human readable.

At this point the team feels like CancelOrderRequest and all it’s members are clear enough. There’s little risk in the ShopperCancelReason.

At this point, the final model looks roughly like this

workflow CancelOrder =

input: CancelOrderRequest

output:

| ShopperOrderCanceled

| OrderCancelFailed

data CancelOrderRequest = {

OrderId: OrderId

Reason: ShopperCancelReason

}

data OrderId =

constraints: Should be unique. Doesn't need to be human readable.

data ShopperCancelReason = // TODO

data ShopperOrderCanceled = // TODO

data OrderCancelFailed = // TODO

Simple Syntax

Remember these data models are meant for collaboration with non-developers. The syntax should be intuitive enough for non-developers to read, but rigorous enough to minimize ambiguity.

I think the syntax use above works pretty well. The short of it is

workflowkeyword to denote the highlevel process that turns commands into eventsinput:andoutput:indented under the workflow to denote the input command and output events

datato denote the shape of information. For example, what information the input command should include.|for alternative data options (e.g.data Answers = | Yes | No){}for groups of data- The

Field Name: Data Typeformat is a bit a bit program-y. It might help to explain it like fields on a form. E.g. Delivery Address and Billing Address might be different fields but share the same Address rules.

- The

constraints:Note any requirements on data. Can just be a sentence or a bullet list describing the requirements.

I’d guess many readers can intuit most of these rules without help though.

Trickier examples - Cart Contents

The previous example went pretty smoothly. But this wasn’t the case for many examples from our explorations. Several data models revealed significant gaps in both the event storm and our shared understanding.

Cart Contents

For example, the cart contents model revealed a modeling gap.

data CartContents = {

customer identifier of CustomerIdentifier

seller identifier of Seller ID

line items of CartLineItem list

}

It turns out carts are specific by customer and seller. A users is not intended to shop across multiple sellers and then check out. This particular ecommerce platform focuses on individual sellers creating shopping experiences.

Also critically, the customer identifier might not be the ID of a logged in user. A user might start a cart without an account.

data CustomerIdentifier =

constraints:

not necessarily a registered user, may identify a session of a user that isn't logged in

must be unique

Picking

The warehouse picking process revealed even more hidden assumptions, and even resulted in changes to the overall event storm model.

A few of the key moments included.

- How does this picker know where to get each item?

- The warehouse location is important SKU data, and we’d forgotten about it

- What do you mean by the picker signs off? Is that something that’s tracked?

- We’d missed the whole expectation that warehouse workers need to sign on orders they picked. It’s a significant policy and performance metric.

- What happens if an item is shorted?

- Generally try to set it aside if the order can be completed relatively soon. Otherwise, they’ll charge only for the items shipped.

- Importantly, we need to be able to handle partial charges and multiple charges per order if parts of an order ship separately.

The order picking model ended up about like this

workflow Mark Order Picking =

input: OrderId * Picker Id

output:

| Order Picking Initiated of OrderId

data Picker Id = unique, represents warehouse employee fulfilling the order

workflow Pick Order =

input: Order Items

output:

| Package Assembled For shipment

| Inventory Short

data Order Items =

list of SKUs, Quantities, and warehouse location (Bin location?)

data Package Assembled for Shipment =

Order Id * Packer Sign off??

data Packer Sign off = could just be name of person who filled the order. Just want to know who did it

data Inventory Short = {

Order Id of OrderId

Shorted Item of list of SKUs and quantities

SetAsideLocation of Bin Location

}

workflow Capture Payment =

input: Order Id * Payment Authorization * payment amount

output:

| Payment Captured of Payment Reference

| Token Expired

When to Stop - Stable, Incremental, Additive

This data modelling approach benefits from several types of incremental progress. Each workflow stands on its own (out of the larger event storm), and the data is also progressively clarified from the top-down. This means the team can work in complete chunks, prioritize the chucks most likely to effect the big picture, and stop whenever they feel confident that overall risk to the model is low enough.

Summary

Data models were a surprisingly effective way to elaborate on an Event Storm and uncover hidden assumptions missed by the higher-level model. This reduces the chances of programmers unhappily rewriting code to fit what business people knew all along, but didn’t know to share.

By choosing notation wisely, these data models can be easy for non-technical people to read but also rigorous enough to make gaps apparent.

I was surprised how much this data phase reveals about the business, and how much it led to rework of the overall event storm.